1. Preparing our dataset¶

These recommendations are so on point! How does this playlist know me so well?

Over the past few years, streaming services with huge catalogs have become the primary means through which most people listen to their favorite music. But at the same time, the sheer amount of music on offer can mean users might be a bit overwhelmed when trying to look for newer music that suits their tastes.

For this reason, streaming services have looked into means of categorizing music to allow for personalized recommendations. One method involves direct analysis of the raw audio information in a given song, scoring the raw data on a variety of metrics. Today, we'll be examining data compiled by a research group known as The Echo Nest. Our goal is to look through this dataset and classify songs as being either 'Hip-Hop' or 'Rock' - all without listening to a single one ourselves. In doing so, we will learn how to clean our data, do some exploratory data visualization, and use feature reduction towards the goal of feeding our data through some simple machine learning algorithms, such as decision trees and logistic regression.

To begin with, let's load the metadata about our tracks alongside the track metrics compiled by The Echo Nest. A song is about more than its title, artist, and number of listens. We have another dataset that has musical features of each track such as danceability and acousticness on a scale from -1 to 1. These exist in two different files, which are in different formats - CSV and JSON. While CSV is a popular file format for denoting tabular data, JSON is another common file format in which databases often return the results of a given query.

Let's start by creating two pandas DataFrames out of these files that we can merge so we have features and labels (often also referred to as X and y) for the classification later on.

import pandas as pd

# Read in track metadata with genre labels

tracks = pd.read_csv('datasets/fma-rock-vs-hiphop.csv')

# Read in track metrics with the features

echonest_metrics = pd.read_json('datasets/echonest-metrics.json', precise_float=True)

# Merge the relevant columns of tracks and echonest_metrics

echo_tracks = pd.merge(echonest_metrics, tracks[['track_id', 'genre_top']], on='track_id', how='inner')

# Inspect the resultant dataframe

echo_tracks.info()

%%nose

def test_tracks_read():

try:

pd.testing.assert_frame_equal(tracks, pd.read_csv('datasets/fma-rock-vs-hiphop.csv'))

except AssertionError:

assert False, "The tracks data frame was not read in correctly."

def test_metrics_read():

ech_met_test = pd.read_json('datasets/echonest-metrics.json', precise_float=True)

try:

pd.testing.assert_frame_equal(echonest_metrics, ech_met_test)

except AssertionError:

assert False, "The echonest_metrics data frame was not read in correctly."

def test_merged_shape():

merged_test = echonest_metrics.merge(tracks[['genre_top', 'track_id']], on='track_id')

try:

pd.testing.assert_frame_equal(echo_tracks, merged_test)

except AssertionError:

assert False, ('The two datasets should be merged on matching track_id values '

'keeping only the track_id and genre_top columns of tracks.')

2. Pairwise relationships between continuous variables¶

We typically want to avoid using variables that have strong correlations with each other -- hence avoiding feature redundancy -- for a few reasons:

- To keep the model simple and improve interpretability (with many features, we run the risk of overfitting).

- When our datasets are very large, using fewer features can drastically speed up our computation time.

To get a sense of whether there are any strongly correlated features in our data, we will use built-in functions in the pandas package.

# Create a correlation matrix

corr_metrics = echo_tracks.corr()

corr_metrics.style.background_gradient()

%%nose

def test_corr_matrix():

assert all(corr_metrics == echonest_metrics.corr()) and isinstance(corr_metrics, pd.core.frame.DataFrame), \

'The correlation matrix can be computed using the .corr() method.'

3. Splitting our data¶

As mentioned earlier, it can be particularly useful to simplify our models and use as few features as necessary to achieve the best result. Since we didn't find any particularly strong correlations between our features, we can now split our data into an array containing our features, and another containing the labels - the genre of the track.

Once we have split the data into these arrays, we will perform some preprocessing steps to optimize our model development.

# Import train_test_split function and Decision tree classifier

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Create features

features = echo_tracks.drop(["genre_top", "track_id"], axis=1).values

# Create labels

labels = echo_tracks["genre_top"].values

# Split our data

train_features, test_features, train_labels, test_labels = train_test_split(features, labels,

random_state=10)

%%nose

import sys

def test_features_labels():

assert features.shape == (4802, 8), \

"""Did you drop "genre_top" from echo_tracks, and store all remaining values as features?"""

assert labels.shape == (4802,), \

"""Did you store values from the "genre_top" column as labels?"""

def test_train_test_split_import():

assert 'sklearn.model_selection' in list(sys.modules.keys()), \

'Have you imported train_test_split from sklearn.model_selection?'

def test_train_test_split():

train_test_res = train_test_split(features, labels, random_state=10)

assert (train_features == train_test_res[0]).all(), \

'Did you correctly call the train_test_split function?'

def test_correct_split():

assert train_features.shape == (3601, 8), \

"""Did you correctly split the data? Expected a different shape for train_features."""

assert test_features.shape == (1201, 8), \

"""Did you correctly split the data? Expected a different shape for test_features."""

assert train_labels.shape == (3601,), \

"""Did you correctly split the data? Expected a different shape for train_labels."""

assert test_labels.shape == (1201,), \

"""Did you correctly split the data? Expected a different shape for test_labels."""

4. Normalizing the feature data¶

As mentioned earlier, it can be particularly useful to simplify our models and use as few features as necessary to achieve the best result. Since we didn't find any particular strong correlations between our features, we can instead use a common approach to reduce the number of features called principal component analysis (PCA).

It is possible that the variance between genres can be explained by just a few features in the dataset. PCA rotates the data along the axis of highest variance, thus allowing us to determine the relative contribution of each feature of our data towards the variance between classes.

However, since PCA uses the absolute variance of a feature to rotate the data, a feature with a broader range of values will overpower and bias the algorithm relative to the other features. To avoid this, we must first normalize our train and test features. There are a few methods to do this, but a common way is through standardization, such that all features have a mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1 (the resultant is a z-score).

# Import the StandardScaler

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

# Scale the features and set the values to a new variable

scaler = StandardScaler()

# Keep only numeric columns in train_features and test_features

numeric_train_features = train_features[:, :13]

numeric_test_features = test_features[:, :13]

# Scale train_features and test_features

scaled_train_features = scaler.fit_transform(numeric_train_features)

scaled_test_features = scaler.transform(numeric_test_features)

%%nose

import sys

import numpy as np

# def test_labels_df():

# try:

# pd.testing.assert_series_equal(labels, echo_tracks['genre_top'])

# except AssertionError:

# assert False, 'Does your labels DataFrame only contain the genre_top column?'

def test_standardscaler_import():

assert 'sklearn.preprocessing' in list(sys.modules.keys()), \

'The StandardScaler can be imported from sklearn.preprocessing.'

def test_scaled_features():

assert scaled_train_features[0].tolist() == [-1.3189452160155823,

-1.748936113215404,

0.5183796247907855,

-0.2981419458739739,

-0.19909374640763283,

-0.41175479316875396,

-0.911269482360871,

-0.3436413082337475], \

"Use the StandardScaler's fit_transform method on train_features."

assert scaled_test_features[0].tolist() == [-1.3182917030552226,

-1.6238218896488739,

1.3841707828629735,

-1.3119421397560926,

2.1929908647262364,

0.03499652489786962,

1.9228785168921492,

-0.2813786091336706], \

"Use the StandardScaler's transform method on test_features."

5. Principal Component Analysis on our scaled data¶

Now that we have preprocessed our data, we are ready to use PCA to determine by how much we can reduce the dimensionality of our data. We can use scree-plots and cumulative explained ratio plots to find the number of components to use in further analyses.

Scree-plots display the number of components against the variance explained by each component, sorted in descending order of variance. Scree-plots help us get a better sense of which components explain a sufficient amount of variance in our data. When using scree plots, an 'elbow' (a steep drop from one data point to the next) in the plot is typically used to decide on an appropriate cutoff.

# This is just to make plots appear in the notebook

%matplotlib inline

# Import our plotting module, and PCA class

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

# Get our explained variance ratios from PCA using all features

pca = PCA()

pca.fit(scaled_train_features)

exp_variance = pca.explained_variance_ratio_

# plot the explained variance using a barplot

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.bar(range(pca.n_components_), exp_variance)

ax.set_xlabel('Principal Component #')

%%nose

import sklearn

import numpy as np

import sys

def test_pca_import():

assert ('sklearn.decomposition' in list(sys.modules.keys())), \

'Have you imported the PCA object from sklearn.decomposition?'

def test_pca_obj():

assert isinstance(pca, sklearn.decomposition.PCA), \

"Use scikit-learn's PCA() object to create your own PCA object here."

def test_exp_variance():

rounded_array = exp_variance

rounder = lambda t: round(t, ndigits = 2)

vectorized_round = np.vectorize(rounder)

assert (vectorized_round(exp_variance)).all() == np.array([0.24, 0.18, 0.14, 0.13, 0.11, 0.09, 0.07, 0.05]).all(), \

'Following the PCA fit, the explained variance ratios can be obtained via the explained_variance_ratio_ method.'

def test_scree_plot():

expected_xticks = [float(n) for n in list(range(-1, 9))]

assert list(ax.get_xticks()) == expected_xticks, \

'Plot the number of pca components (on the x-axis) against the explained variance (on the y-axis).'

6. Further visualization of PCA¶

Unfortunately, there does not appear to be a clear elbow in this scree plot, which means it is not straightforward to find the number of intrinsic dimensions using this method.

But all is not lost! Instead, we can also look at the cumulative explained variance plot to determine how many features are required to explain, say, about 85% of the variance (cutoffs are somewhat arbitrary here, and usually decided upon by 'rules of thumb'). Once we determine the appropriate number of components, we can perform PCA with that many components, ideally reducing the dimensionality of our data.

import numpy as np

# Calculate the cumulative explained variance

cum_exp_variance = np.cumsum(exp_variance)

# Plot the cumulative explained variance and draw a dashed line at 0.85.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(cum_exp_variance)

ax.axhline(y=0.85, linestyle='--')

%%nose

import sys

def test_np_import():

assert 'numpy' in list(sys.modules.keys()), \

'Have you imported numpy?'

def test_cumsum():

cum_exp_variance_correct = np.cumsum(exp_variance)

assert all(cum_exp_variance == cum_exp_variance_correct), \

'Use np.cumsum to calculate the cumulative sum of the exp_variance array.'

# def test_n_comp():

# assert n_components == 5, \

# ('Check the values in cum_exp_variance if it is difficult '

# 'to determine the number of components from the plot.')

# def test_trans_pca():

# pca_test = PCA(n_components, random_state=10)

# pca_test.fit(scaled_train_features)

# assert (pca_projection == pca_test.transform(scaled_train_features)).all(), \

# 'Transform the scaled features and assign them to the pca_projection variable.'

7. Projecting on to our features¶

We saw from the plot that 6 features (remember indexing starts at 0) can explain 85% of the variance!

Therefore, we can use 6 components to perform PCA and reduce the dimensionality of our train and test features.

# Perform PCA with the chosen number of components and project data onto components

pca = PCA(n_components=6, random_state=10)

# Fit and transform the scaled training features using pca

train_pca = pca.fit_transform(scaled_train_features)

# Fit and transform the scaled test features using pca

test_pca = pca.transform(scaled_test_features)

%%nose

import sys

import sklearn

def test_pca_import():

assert ('sklearn.decomposition' in list(sys.modules.keys())), \

'Have you imported the PCA object from sklearn.decomposition?'

def test_pca_obj():

assert isinstance(pca, sklearn.decomposition.PCA), \

"Use scikit-learn's PCA() object to create your own PCA object here."

def test_trans_pca():

pca_copy = PCA(n_components=6, random_state=10)

pca_copy.fit(scaled_train_features)

assert train_pca.all() == pca_copy.transform(scaled_train_features).all(), \

'Fit and transform the scaled training features and assign them to the train_pca variable.'

pca_test = pca_copy.transform(scaled_test_features)

assert test_pca.all() == pca_copy.transform(scaled_test_features).all()

8. Train a decision tree to classify genre¶

Now we can use the lower dimensional PCA projection of the data to classify songs into genres.

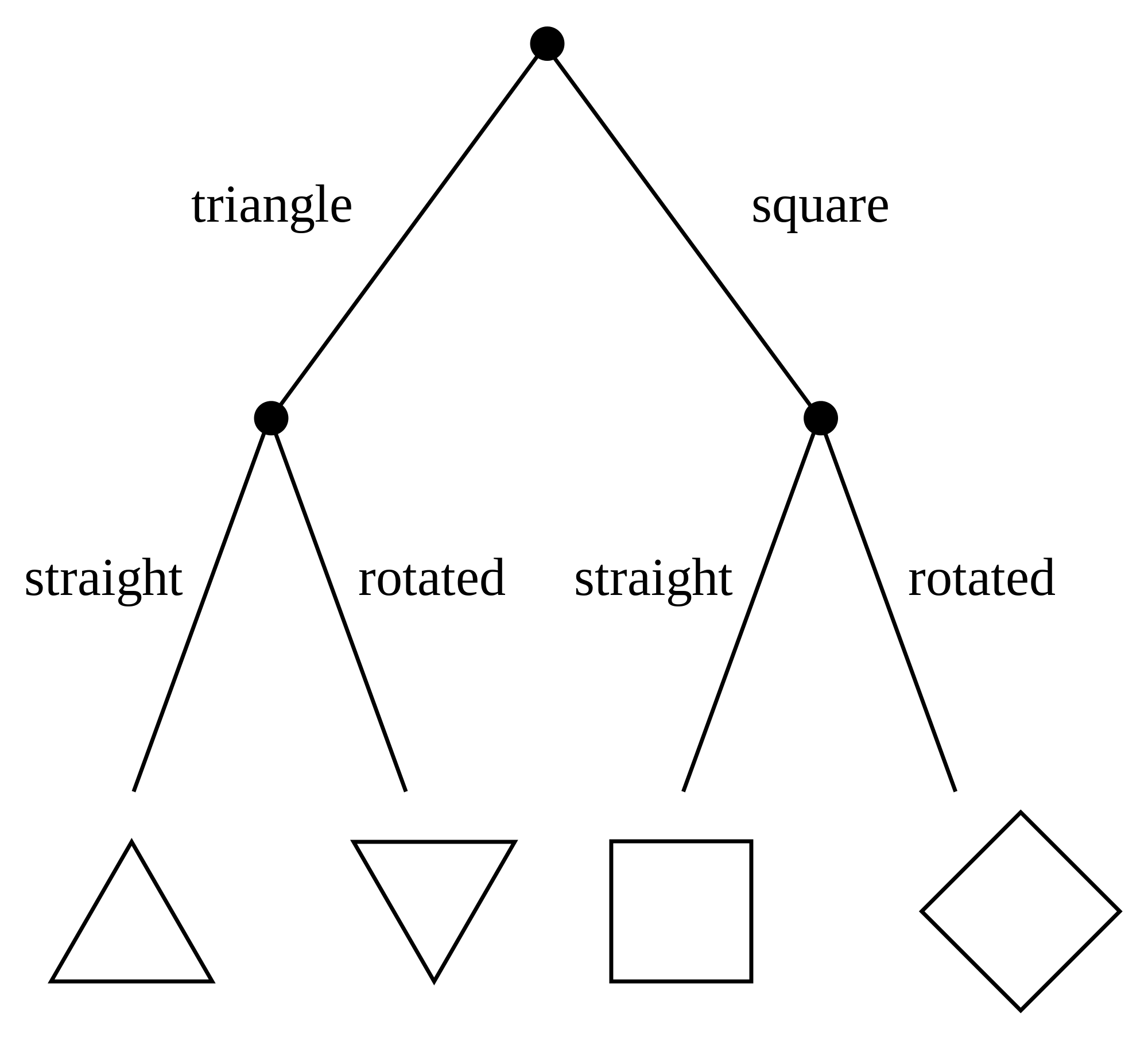

Here, we will be using a simple algorithm known as a decision tree. Decision trees are rule-based classifiers that take in features and follow a 'tree structure' of binary decisions to ultimately classify a data point into one of two or more categories. In addition to being easy to both use and interpret, decision trees allow us to visualize the 'logic flowchart' that the model generates from the training data.

Here is an example of a decision tree that demonstrates the process by which an input image (in this case, of a shape) might be classified based on the number of sides it has and whether it is rotated.

# Import Decision tree classifier

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

# Train our decision tree

tree = DecisionTreeClassifier(random_state=10)

tree.fit(train_pca, train_labels)

# Predict the labels for the test data

pred_labels_tree = tree.predict(test_pca)

%%nose

import sys

# def test_train_test_split_import():

# assert 'sklearn.model_selection' in list(sys.modules.keys()), \

# 'Have you imported train_test_split from sklearn.model_selection?'

def test_decision_tree_import():

assert 'sklearn.tree' in list(sys.modules.keys()), \

'Have you imported DecisionTreeClassifier from sklearn.tree?'

# def test_train_test_split():

# train_test_res = train_test_split(pca_projection, labels, random_state=10)

# assert (train_features == train_test_res[0]).all(), \

# 'Did you correctly call the train_test_split function?'

def test_tree():

assert tree.get_params() == DecisionTreeClassifier(random_state=10).get_params(), \

'Did you create the decision tree correctly?'

def test_tree_fit():

assert hasattr(tree, 'classes_'), \

'Did you fit the tree to the training data?'

def test_tree_pred():

assert (pred_labels_tree == 'Rock').sum() == 971, \

'Did you correctly use the fitted tree object to make a prediction from test_pca?'

9. Compare our decision tree to a logistic regression¶

Although our tree's performance is decent, it's a bad idea to immediately assume that it's therefore the perfect tool for this job -- there's always the possibility of other models that will perform even better! It's always a worthwhile idea to at least test a few other algorithms and find the one that's best for our data.

Sometimes simplest is best, and so we will start by applying logistic regression. Logistic regression makes use of what's called the logistic function to calculate the odds that a given data point belongs to a given class. Once we have both models, we can compare them on a few performance metrics, such as false positive and false negative rate (or how many points are inaccurately classified).

# Import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

# Train our logisitic regression

logreg = LogisticRegression(random_state=10)

logreg.fit(train_pca, train_labels)

pred_labels_logit = logreg.predict(test_pca)

# Create the classification report for both models

from sklearn.metrics import classification_report

class_rep_tree = classification_report(test_labels, pred_labels_tree)

class_rep_log = classification_report(test_labels, pred_labels_logit)

print("Decision Tree: \n", class_rep_tree)

print("Logistic Regression: \n", class_rep_log)

%%nose

def test_logreg():

assert logreg.get_params() == LogisticRegression(random_state=10).get_params(), \

'The logreg variable should be created using LogisticRegression().'

def test_logreg_pred():

assert abs((pred_labels_logit == 'Rock').sum() - 1028) < 7, \

'The labels should be predicted from the test_features.'

def test_class_rep_tree():

assert isinstance(class_rep_tree, str), \

'Did you create the classification report correctly for the decision tree?'

def test_class_rep_log():

assert isinstance(class_rep_log, str), \

'Did you create the classification report correctly for the logistic regression?'

10. Balance our data for greater performance¶

Both our models do similarly well, boasting an average precision of 87% each. However, looking at our classification report, we can see that rock songs are fairly well classified, but hip-hop songs are disproportionately misclassified as rock songs.

Why might this be the case? Well, just by looking at the number of data points we have for each class, we see that we have far more data points for the rock classification than for hip-hop, potentially skewing our model's ability to distinguish between classes. This also tells us that most of our model's accuracy is driven by its ability to classify just rock songs, which is less than ideal.

To account for this, we can weight the value of a correct classification in each class inversely to the occurrence of data points for each class. Since a correct classification for "Rock" is not more important than a correct classification for "Hip-Hop" (and vice versa), we only need to account for differences in sample size of our data points when weighting our classes here, and not relative importance of each class.

# Subset a balanced proportion of data points

hop_only = echo_tracks.loc[echo_tracks['genre_top'] == 'Hip-Hop']

rock_only = echo_tracks.loc[echo_tracks['genre_top'] == 'Rock']

# subset only the rock songs, and take a sample the same size as there are hip-hop songs

rock_only = rock_only.sample(hop_only.shape[0], random_state=10)

# concatenate the dataframes hop_only and rock_only

rock_hop_bal = pd.concat([rock_only, hop_only])

# The features, labels, and pca projection are created for the balanced dataframe

features = rock_hop_bal.drop(['genre_top', 'track_id'], axis=1)

labels = rock_hop_bal['genre_top']

# Redefine the train and test set with the pca_projection from the balanced data

train_features, test_features, train_labels, test_labels = train_test_split(

features, labels, random_state=10)

train_pca = pca.fit_transform(scaler.fit_transform(train_features))

test_pca = pca.transform(scaler.transform(test_features))

%%nose

def test_hop_only():

try:

pd.testing.assert_frame_equal(hop_only, echo_tracks.loc[echo_tracks['genre_top'] == 'Hip-Hop'])

except AssertionError:

assert False, "The hop_only data frame was not assigned correctly."

def test_rock_only():

try:

pd.testing.assert_frame_equal(

rock_only, echo_tracks.loc[echo_tracks['genre_top'] == 'Rock'].sample(hop_only.shape[0], random_state=10))

except AssertionError:

assert False, "The rock_only data frame was not assigned correctly."

def test_rock_hop_bal():

hop_only = echo_tracks.loc[echo_tracks['genre_top'] == 'Hip-Hop']

rock_only = echo_tracks.loc[echo_tracks['genre_top'] == 'Rock'].sample(hop_only.shape[0], random_state=10)

try:

pd.testing.assert_frame_equal(

rock_hop_bal, pd.concat([rock_only, hop_only]))

except AssertionError:

assert False, "The rock_hop_bal data frame was not assigned correctly."

def test_train_features():

assert round(train_pca[0][0], 4) == -0.6434 and round(test_pca[0][0], 4) == 0.4368, \

'The train_test_split was not performed correctly.'

11. Does balancing our dataset improve model bias?¶

We've now balanced our dataset, but in doing so, we've removed a lot of data points that might have been crucial to training our models. Let's test to see if balancing our data improves model bias towards the "Rock" classification while retaining overall classification performance.

Note that we have already reduced the size of our dataset and will go forward without applying any dimensionality reduction. In practice, we would consider dimensionality reduction more rigorously when dealing with vastly large datasets and when computation times become prohibitively large.

# Train our decision tree on the balanced data

tree = DecisionTreeClassifier(random_state=10)

tree.fit(train_pca, train_labels)

pred_labels_tree = tree.predict(test_pca)

# Train our logistic regression on the balanced data

logreg = LogisticRegression(random_state=10)

logreg.fit(train_pca, train_labels)

pred_labels_logit = logreg.predict(test_pca)

# Compare the models

print("Decision Tree: \n", classification_report(test_labels, pred_labels_tree))

print("Logistic Regression: \n", classification_report(test_labels, pred_labels_logit))

%%nose

def test_tree_bal():

assert (pred_labels_tree == 'Rock').sum() == 213, \

'The pred_labels_tree variable should contain the predicted labels from the test_features.'

def test_logit_bal():

assert (pred_labels_logit == 'Rock').sum() == 219, \

'The pred_labels_logit variable should contain the predicted labels from the test_features.'

12. Using cross-validation to evaluate our models¶

Success! Balancing our data has removed bias towards the more prevalent class. To get a good sense of how well our models are actually performing, we can apply what's called cross-validation (CV). This step allows us to compare models in a more rigorous fashion.

Before we can perform cross-validation we will need to create pipelines to scale our data, perform PCA, and instantiate our model of choice - DecisionTreeClassifier or LogisticRegression.

Since the way our data is split into train and test sets can impact model performance, CV attempts to split the data multiple ways and test the model on each of the splits. Although there are many different CV methods, all with their own advantages and disadvantages, we will use what's known as K-fold CV here. K-fold first splits the data into K different, equally sized subsets. Then, it iteratively uses each subset as a test set while using the remainder of the data as train sets. Finally, we can then aggregate the results from each fold for a final model performance score.

from sklearn.model_selection import KFold, cross_val_score

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

tree_pipe = Pipeline([("scaler", StandardScaler()), ("pca", PCA(n_components=6)),

("tree", DecisionTreeClassifier(random_state=10))])

logreg_pipe = Pipeline([("scaler", StandardScaler()), ("pca", PCA(n_components=6)),

("logreg", LogisticRegression(random_state=10))])

# Set up our K-fold cross-validation

kf = KFold(10)

# Train our models using KFold cv

tree_score = cross_val_score(tree_pipe, features, labels, cv=kf)

logit_score = cross_val_score(logreg_pipe, features, labels, cv=kf)

# Print the mean of each array o scores

print("Decision Tree:", np.mean(tree_score), "Logistic Regression:", np.mean(logit_score))

%%nose

def test_kf():

assert kf.__repr__() == 'KFold(n_splits=10, random_state=None, shuffle=False)', \

'The k-fold cross-validation was not setup correctly.'

def test_tree_score():

assert np.isclose(round((tree_score.sum() / tree_score.shape[0]), 4), 0.722, atol=1e-3), \

'The tree_score was not calculated correctly.'

def test_log_score():

assert np.isclose(round((logit_score.sum() / logit_score.shape[0]), 4), 0.7731, atol=1e-3), \

'The logit_score was not calculated correctly.'