1. Cosmetics, chemicals... it's complicated¶

Whenever I want to try a new cosmetic item, it's so difficult to choose. It's actually more than difficult. It's sometimes scary because new items that I've never tried end up giving me skin trouble. We know the information we need is on the back of each product, but it's really hard to interpret those ingredient lists unless you're a chemist. You may be able to relate to this situation.

So instead of buying and hoping for the best, why don't we use data science to help us predict which products may be good fits for us? In this notebook, we are going to create a content-based recommendation system where the 'content' will be the chemical components of cosmetics. Specifically, we will process ingredient lists for 1472 cosmetics on Sephora via word embedding, then visualize ingredient similarity using a machine learning method called t-SNE and an interactive visualization library called Bokeh. Let's inspect our data first.

# Import libraries

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from sklearn.manifold import TSNE

# Load the data

df = pd.read_csv('datasets/cosmetics.csv')

# Check the first five rows

display(df.sample(5))

# Inspect the types of products

display(df['Label'].value_counts())

%%nose

# %%nose needs to be included at the beginning of every @tests cell

# One or more tests of the student's code

# The @solution should pass the tests

# The purpose of the tests is to try to catch common errors and

# to give the student a hint on how to resolve these errors

# last_output = _

def strip_comment_lines(cell_input):

"""Returns cell input string with comment lines removed."""

return '\n'.join(line for line in cell_input.splitlines() if not line.startswith('#'))

last_input = strip_comment_lines(In[-2])

def test_importing_library():

assert 'pd' in globals(), 'Did you import the pandas library aliased as pd?'

assert 'np' in globals(), 'Did you import the numpy library aliased as np?'

assert 'TSNE' in globals(), 'Did you import the TSNE from sklearn.manifold library?'

def test_importing_data():

correct_df = pd.read_csv('datasets/cosmetics.csv')

assert correct_df.equals(df), 'The DataFrame df should contain the data in cosmetics.csv.'

def test_sample_command():

assert 'df.sample(' in last_input, \

"Did you use the sample() method to inspect the data?"

def test_sample_command():

assert 'df.Label.value_counts()' in last_input or "df['Label'].value_counts()" in last_input, \

"Did you use the value_counts() method on df.Label (or df['Label']) to inspect the cosmetic category counts?"

# def test_head_output():

# try:

# assert ("Label" in last_output.to_string() and len(last_output) == 5)

# except AttributeError:

# assert False, \

# "Please use df.sample() as the last line of code in the cell to inspect the data, not the display() or print() functions."

# except AssertionError:

# assert False, \

# "Hmm, the output of the cell is not what we expected. You should see Label as the first column of the df DataFrame, which should have five rows displayed."

2. Focus on one product category and one skin type¶

There are six categories of product in our data (moisturizers, cleansers, face masks, eye creams, and sun protection) and there are five different skin types (combination, dry, normal, oily and sensitive). Because individuals have different product needs as well as different skin types, let's set up our workflow so its outputs (a t-SNE model and a visualization of that model) can be customized. For the example in this notebook, let's focus in on moisturizers for those with dry skin by filtering the data accordingly.

# Filter for moisturizers

moisturizers = df[df['Label'] == 'Moisturizer']

# Filter for dry skin as well

moisturizers_dry = moisturizers[moisturizers['Dry'] == 1]

# Reset index

moisturizers_dry = moisturizers_dry.reset_index(drop=True)

%%nose

# %%nose needs to be included at the beginning of every @tests cell

# One or more tests of the student's code

# The @solution should pass the tests

# The purpose of the tests is to try to catch common errors and

# to give the student a hint on how to resolve these errors

correct_moisturizers = df[df['Label'] == 'Moisturizer']

def test_columns_list():

assert list(moisturizers_dry.columns) == ['Label', 'Brand', 'Name', 'Price', 'Rank', 'Ingredients', 'Combination', 'Dry', 'Normal', 'Oily', 'Sensitive'], \

'At least one column name is incorrect or out of order.'

def test_moisturizers():

assert correct_moisturizers.equals(moisturizers), 'The intermediate moisturizers DataFrame does not contain the data in cosmetics.csv filtered for the label "Moisturizer".'

# def test_moisturizers_dry():

# correct_moisturizers_dry = correct_moisturizers[correct_moisturizers['Dry'] == 1]

# correct_moisturizers_dry.reset_index(drop = True)

# assert correct_moisturizers_dry.equals(moisturizers_dry), 'The moisturizers_dry DataFrame does not contain the data in cosmetics.csv filtered for the label "Moisturizer" then for 1 in the "Dry" column, with the index reset.'

def test_index():

assert (moisturizers_dry.index == range(0, 190, 1)).all(), \

'Did you filter the moisturizers DataFrame for 1 in the "Dry" column, then reset the index of the DataFrame? The index should range from 0 to 189.'

3. Tokenizing the ingredients¶

To get to our end goal of comparing ingredients in each product, we first need to do some preprocessing tasks and bookkeeping of the actual words in each product's ingredients list. The first step will be tokenizing the list of ingredients in Ingredients column. After splitting them into tokens, we'll make a binary bag of words. Then we will create a dictionary with the tokens, ingredient_idx, which will have the following format:

{ "ingredient": index value, … }

# Initialize dictionary, list, and initial index

ingredient_idx = {}

corpus = []

idx = 0

# For loop for tokenization

for i in range(len(moisturizers_dry)):

ingredients = moisturizers_dry['Ingredients'][i]

ingredients_lower = ingredients.lower()

tokens = ingredients_lower.split(', ')

corpus.append(tokens)

for ingredient in tokens:

if ingredient not in ingredient_idx:

ingredient_idx[ingredient] = idx

idx += 1

# Check the result

print("The index for decyl oleate is", ingredient_idx['decyl oleate'])

%%nose

def test_ingredient_idx_len():

assert len(ingredient_idx) == 2233, \

'The length of ingredient_idx should be 2233, but it isn\'t.'

def test_ingredient_idx_content():

assert [ingredient_idx['paraffin'], ingredient_idx['niacin'], ingredient_idx['water']] == [20, 22, 23], \

'The items of ingredient_idx are not what we expected. Did you correctly index each token?'

def test_corpus_len():

assert (len(corpus) == 190), \

'The length of corpus should be 190, but it isn\'t.'

def test_output_index():

assert ingredient_idx['decyl oleate'] == 25, \

'The integer in decyl_oleate_index is not what we expected. Please check if you have correctly input the ingredient.'

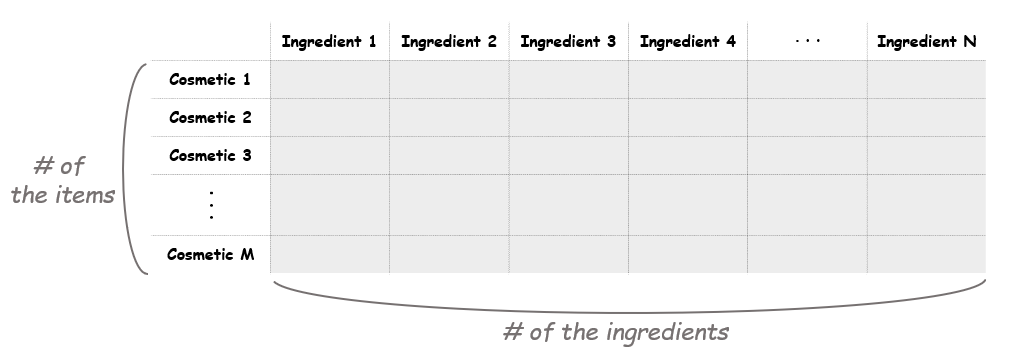

4. Initializing a document-term matrix (DTM)¶

The next step is making a document-term matrix (DTM). Here each cosmetic product will correspond to a document, and each chemical composition will correspond to a term. This means we can think of the matrix as a “cosmetic-ingredient” matrix. The size of the matrix should be as the picture shown below.

# Get the number of items and tokens

M = moisturizers_dry.shape[0]

N = len(ingredient_idx)

# Initialize a matrix of zeros

A = np.zeros((M, N))

%%nose

# %%nose needs to be included at the beginning of every @tests cell

def test_M_num():

assert M == 190, 'The value of M is incorrect. It should be 190.'

def test_N_num():

assert N == 2233, 'The value of N is incorrect. It should be 2233.'

def test_A_zeros():

assert np.sum(A) == 0, 'The values of A do not all sum to 0 and they should.'

def test_A_shape():

assert A.shape == (190, 2233), 'The shape of the matrix A is not what we expected. It should be (190, 2233).'

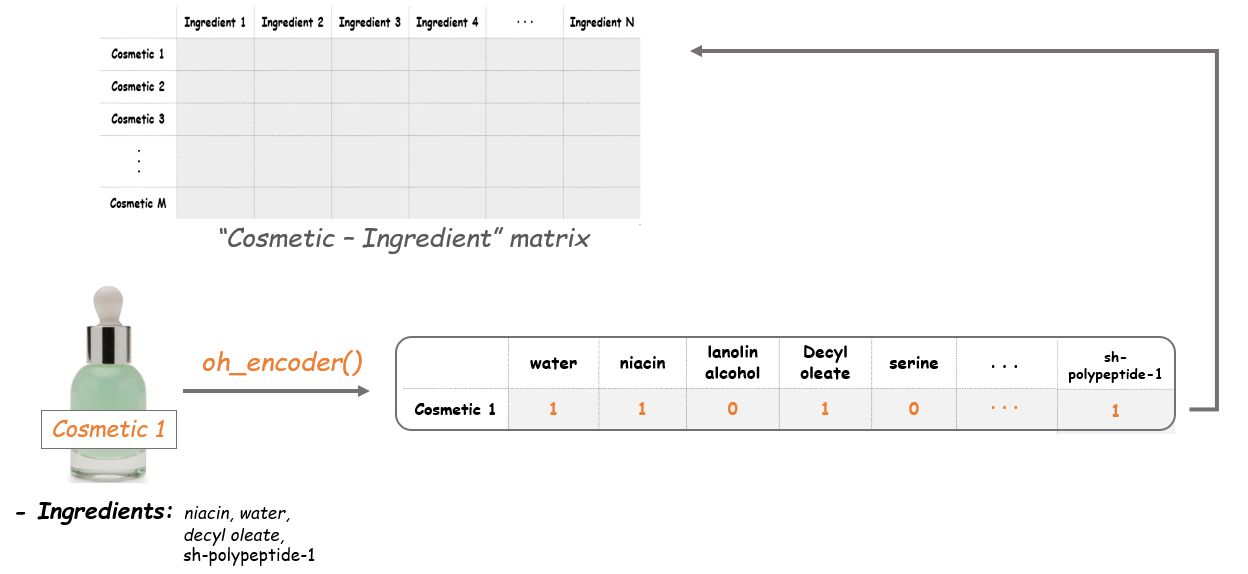

5. Creating a counter function¶

Before we can fill the matrix, let's create a function to count the tokens (i.e., an ingredients list) for each row. Our end goal is to fill the matrix with 1 or 0: if an ingredient is in a cosmetic, the value is 1. If not, it remains 0. The name of this function, oh_encoder, will become clear next.

# Define the oh_encoder function

def oh_encoder(tokens):

x = np.zeros(N)

for ingredient in tokens:

# Get the index for each ingredient

idx = ingredient_idx[ingredient]

# Put 1 at the corresponding indices

x[idx] = 1

return x

%%nose

# %%nose needs to be included at the beginning of every tests cell

# First three values by the correctly defined function

temp = np.asarray(range(2233))

answer = [861, 282, 4077]

def test_oh_encoder():

submit = [np.dot(oh_encoder(corpus[i]), temp) for i in range(3)]

assert answer == submit, \

'The function is not correctly defined. The oh_encoder() function with the input values 1 through 5 should return the following results: 42, 7, 58, 78, 82.'

6. The Cosmetic-Ingredient matrix!¶

Now we'll apply the oh_encoder() functon to the tokens in corpus and set the values at each row of this matrix. So the result will tell us what ingredients each item is composed of. For example, if a cosmetic item contains water, niacin, decyl aleate and sh-polypeptide-1, the outcome of this item will be as follows.

# Make a document-term matrix

i = 0

for tokens in corpus:

A[i, :] = oh_encoder(tokens)

i += 1

%%nose

# %%nose needs to be included at the beginning of every @tests cell

correct_A = np.zeros((M, N))

i = 0

for tokens in corpus:

correct_A[i, :] = oh_encoder(tokens)

i += 1

def test_A_matrix():

assert (correct_A == A).all(), \

'The contents of A are not what we expected. Please reread the instructions and check the hint if necessary.'

7. Dimension reduction with t-SNE¶

The dimensions of the existing matrix is (190, 2233), which means there are 2233 features in our data. For visualization, we should downsize this into two dimensions. We'll use t-SNE for reducing the dimension of the data here.

T-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) is a nonlinear dimensionality reduction technique that is well-suited for embedding high-dimensional data for visualization in a low-dimensional space of two or three dimensions. Specifically, this technique can reduce the dimension of data while keeping the similarities between the instances. This enables us to make a plot on the coordinate plane, which can be said as vectorizing. All of these cosmetic items in our data will be vectorized into two-dimensional coordinates, and the distances between the points will indicate the similarities between the items.

# Dimension reduction with t-SNE

model = TSNE(n_components=2, learning_rate=200, random_state=42)

tsne_features = model.fit_transform(A)

# Make X, Y columns

moisturizers_dry['X'] = tsne_features[:, 0]

moisturizers_dry['Y'] = tsne_features[:, 1]

%%nose

# %%nose needs to be included at the beginning of every @tests cell

def test_tsne_features_shape():

assert tsne_features.shape == (190, 2), \

'The shape of tsne_features is not what we expected. It should be (190, 2).'

#answer = '12.48590'

answer = '-0.42638'

def test_tsne_features_value():

assert '%.5f' % tsne_features[:3].sum() == answer, \

'The values of tsne_features are not what we expected. Please check the parameters of the model again.'

def test_X_Y_values():

assert (tsne_features[:, 0] == moisturizers_dry['X']).all(), 'The values for X in moisturizers_dry are not what we expected. Did you correctly assign the columns of tsne_features?'

assert (tsne_features[:, 1] == moisturizers_dry['Y']).all(), 'The values for Y in moisturizers_dry are not what we expected. Did you correctly assign the columns of tsne_features?'

8. Let's map the items with Bokeh¶

We are now ready to start creating our plot. With the t-SNE values, we can plot all our items on the coordinate plane. And the coolest part here is that it will also show us the name, the brand, the price and the rank of each item. Let's make a scatter plot using Bokeh and add a hover tool to show that information. Note that we won't display the plot yet as we will make some more additions to it.

from bokeh.io import show, output_notebook, push_notebook

from bokeh.plotting import figure

from bokeh.models import ColumnDataSource, HoverTool

output_notebook()

# Create a ColumnDataSource

source = ColumnDataSource(moisturizers_dry)

# Create a scatter plot

plot = figure(x_axis_label = 'T-SNE 1',

y_axis_label = 'T-SNE 2',

width = 500, height = 400)

# Add a circle renderer

plot.circle(x = 'X',

y = 'Y',

source = source,

size = 10, color = '#FF7373', alpha = .8)

%%nose

# %%nose needs to be included at the beginning of every @tests cell

last_output = _

from bokeh.io import curdoc

curdoc().add_root(plot)

def test_source():

assert (last_output.data_source.data['Label'] == 'Moisturizer').all() & (last_output.data_source.data['Dry'] == 1).all(), \

"The ColumnDataSource for plot.circle() should be moisturizers_dry."

def test_x_plot_correct():

assert curdoc().to_json_string().find('"x":{"field":"X"}') >=0, \

"The x-argument for plot.circle() should be 'X' and it isn't."

def test_y_plot_correct():

assert curdoc().to_json_string().find('"y":{"field":"Y"}') >= 0, \

"The y-argument for plot.circle() should be 'Y' and it isn't."

def test_bokeh_visible():

assert last_output.visible == True, \

'A plot was not the last output of the cell.'

9. Adding a hover tool¶

Why don't we add a hover tool? Adding a hover tool allows us to check the information of each item whenever the cursor is directly over a glyph. We'll add tooltips with each product's name, brand, price, and rank (i.e., rating).

# Create a HoverTool object

hover = HoverTool(tooltips = [('Item', '@Name'),

('Brand', '@Brand'),

('Price', '$@Price'),

('Rank', '@Rank')])

plot.add_tools(hover)

%%nose

# %%nose needs to be included at the beginning of every @tests cell

import bokeh

from bokeh.io import curdoc

curdoc().add_root(plot)

def test_hover_exists():

assert type(hover) == bokeh.models.tools.HoverTool, \

"The variable hover does not contain a HoverlTool object."

correct_hover_tooltips = [('Item', '@Name'),

('Brand', '@Brand'),

('Price', '$@Price'),

('Rank', '@Rank')]

def test_hover_correct():

assert hover.tooltips == correct_hover_tooltips, \

"hover is not created correctly. Please reread the instructions and check the hint if necessary."

def test_hover_plot_correct():

assert curdoc().to_json_string().find('"tooltips":[["Item","@Name"],["Brand","@Brand"],["Price","$@Price"],["Rank","@Rank"]]'), \

"The hover tool wasn't added to the plot correctly. Please reread the instructions and check the hint if necessary."

10. Mapping the cosmetic items¶

Finally, it's show time! Let's see how the map we've made looks like. Each point on the plot corresponds to the cosmetic items. Then what do the axes mean here? The axes of a t-SNE plot aren't easily interpretable in terms of the original data. Like mentioned above, t-SNE is a visualizing technique to plot high-dimensional data in a low-dimensional space. Therefore, it's not desirable to interpret a t-SNE plot quantitatively.

Instead, what we can get from this map is the distance between the points (which items are close and which are far apart). The closer the distance between the two items is, the more similar the composition they have. Therefore this enables us to compare the items without having any chemistry background.

# Plot the map

show(plot)

%%nose

# %%nose needs to be included at the beginning of every @tests cell

def strip_comment_lines(cell_input):

"""Returns cell input string with comment lines removed."""

return '\n'.join(line for line in cell_input.splitlines() if not line.startswith('#'))

last_input = strip_comment_lines(In[-2])

last_output = _

def test_command_syntax():

assert 'show(plot)' in last_input, \

"Did you call the show() function on the plot variable?"

11. Comparing two products¶

Since there are so many cosmetics and so many ingredients, the plot doesn't have many super obvious patterns that simpler t-SNE plots can have (example). Our plot requires some digging to find insights, but that's okay!

Say we enjoyed a specific product, there's an increased chance we'd enjoy another product that is similar in chemical composition. Say we enjoyed AmorePacific's Color Control Cushion Compact Broad Spectrum SPF 50+. We could find this product on the plot and see if a similar product(s) exist. And it turns out it does! If we look at the points furthest left on the plot, we see LANEIGE's BB Cushion Hydra Radiance SPF 50 essentially overlaps with the AmorePacific product. By looking at the ingredients, we can visually confirm the compositions of the products are similar (though it is difficult to do, which is why we did this analysis in the first place!), plus LANEIGE's version is $22 cheaper and actually has higher ratings.

It's not perfect, but it's useful. In real life, we can actually use our little ingredient-based recommendation engine help us make educated cosmetic purchase choices.

# Print the ingredients of two similar cosmetics

cosmetic_1 = moisturizers_dry[moisturizers_dry['Name'] == "Color Control Cushion Compact Broad Spectrum SPF 50+"]

cosmetic_2 = moisturizers_dry[moisturizers_dry['Name'] == "BB Cushion Hydra Radiance SPF 50"]

# Display each item's data and ingredients

display(cosmetic_1)

print(cosmetic_1.Ingredients.values)

display(cosmetic_2)

print(cosmetic_2.Ingredients.values)

%%nose

def test_nothing():

assert True, "Just run the cell! :)"