1. Import Python libraries¶

A honey bee (Apis).

A honey bee (Apis).

Can a machine identify a bee as a honey bee or a bumble bee? These bees have different behaviors and appearances, but given the variety of backgrounds, positions, and image resolutions, it can be a challenge for machines to tell them apart.

Being able to identify bee species from images is a task that ultimately would allow researchers to more quickly and effectively collect field data. Pollinating bees have critical roles in both ecology and agriculture, and diseases like colony collapse disorder threaten these species. Identifying different species of bees in the wild means that we can better understand the prevalence and growth of these important insects.

A bumble bee (Bombus).

A bumble bee (Bombus).

After loading and pre-processing images, this notebook walks through building a model that can automatically detect honey bees and bumble bees.

# used to change filepaths

import os

import matplotlib as mpl

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from IPython.display import display

%matplotlib inline

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# import Image from PIL

from PIL import Image

from skimage.feature import hog

from skimage.color import rgb2gray

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

# import train_test_split from sklearn's model selection module

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# import SVC from sklearn's svm module

from sklearn.svm import SVC

# import accuracy_score from sklearn's metrics module

from sklearn.metrics import roc_curve, auc, accuracy_score

%%nose

def test_task_1():

assert 'Image' in globals(), \

'Did you forget to import `Image` from `PIL`?'

def test_task_2():

assert 'train_test_split' in globals(), \

'Did you forget to import `train_test_split` from `sklearn.model_selection`?'

def test_task_3():

assert 'SVC' in globals(), \

'Did you forget to import `SVC` from `sklearn.svm`?'

def test_task_4():

assert 'accuracy_score' in globals(), \

'Did you forget to import `accuracy_score` from `sklearn.metrics`?'

2. Display image of each bee type¶

Now that we have all of our imports ready, it is time to look at some images. We will load our labels.csv file into a dataframe called labels, where the index is the image name (e.g. an index of 1036 refers to an image named 1036.jpg) and the genus column tells us the bee type. genus takes the value of either 0.0 (Apis or honey bee) or 1.0 (Bombus or bumble bee).

The function get_image converts an index value from the dataframe into a file path where the image is located, opens the image using the Image object in Pillow, and then returns the image as a numpy array.

We'll use this function to load the sixth Apis image and then the sixth Bombus image in the dataframe.

# load the labels using pandas

labels = pd.read_csv("datasets/labels.csv", index_col=0)

# show the first five rows of the dataframe using head

display(labels.head())

def get_image(row_id, root="datasets/"):

"""

Converts an image number into the file path where the image is located,

opens the image, and returns the image as a numpy array.

"""

filename = "{}.jpg".format(row_id)

file_path = os.path.join(root, filename)

img = Image.open(file_path)

return np.array(img)

# subset the dataframe to just Apis (genus is 0.0) get the value of the sixth item in the index

apis_row = labels[labels.genus == 0.0].index[5]

# show the corresponding image of an Apis

plt.imshow(get_image(apis_row))

plt.show()

# subset the dataframe to just Bombus (genus is 1.0) get the value of the sixth item in the index

bombus_row = labels[labels.genus == 1.0].index[5]

# show the corresponding image of a Bombus

plt.imshow(get_image(bombus_row))

plt.show()

%%nose

def test_task2_0():

assert (bombus_row == 1934), \

'Did you get the sixth row of the index of the subsetted dataframe (labels[labels.genus == 0.0])?'

3. Image manipulation with rgb2gray¶

scikit-image has a number of image processing functions built into the library, for example, converting an image to grayscale. The rgb2gray function computes the luminance of an RGB image using the following formula Y = 0.2125 R + 0.7154 G + 0.0721 B.

Image data is represented as a matrix, where the depth is the number of channels. An RGB image has three channels (red, green, and blue) whereas the returned grayscale image has only one channel. Accordingly, the original color image has the dimensions 100x100x3 but after calling rgb2gray, the resulting grayscale image has only one channel, making the dimensions 100x100x1.

# load a bombus image using our get_image function and bombus_row from the previous cell

bombus = get_image(bombus_row)

# print the shape of the bombus image

print('Color bombus image has shape: ', bombus.shape)

# convert the bombus image to grayscale

gray_bombus = rgb2gray(bombus)

# show the grayscale image

plt.imshow(gray_bombus, cmap=mpl.cm.gray)

# confirm grayscale bombus image only has one channel

print('Grayscale bombus image has shape: ', gray_bombus.shape)

%%nose

import numpy

def test_task3_0():

assert 'bombus' in globals() and bombus.shape == (100, 100, 3), \

'Did you load the image corresponding to `bombus_row` using the `get_image` function and assign it to `bombus`?'

def test_task3_1():

assert gray_bombus.shape == (100, 100) and gray_bombus.max() <= 1, \

'Did you convert `bombus` to grayscale using `rgb2gray`?'

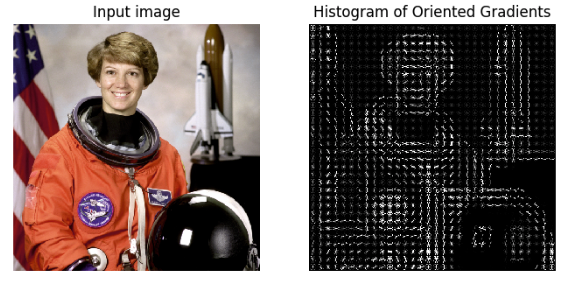

4. Histogram of oriented gradients¶

Now we need to turn these images into something that a machine learning algorithm can understand. Traditional computer vision techniques have relied on mathematical transforms to turn images into useful features. For example, you may want to detect edges of objects in an image, increase the contrast, or filter out particular colors.

We've got a matrix of pixel values, but those don't contain enough interesting information on their own for most algorithms. We need to help the algorithms along by picking out some of the salient features for them using the histogram of oriented gradients (HOG) descriptor. The idea behind HOG is that an object's shape within an image can be inferred by its edges, and a way to identify edges is by looking at the direction of intensity gradients (i.e. changes in luminescence).

An image is divided in a grid fashion into cells, and for the pixels within each cell, a histogram of gradient directions is compiled. To improve invariance to highlights and shadows in an image, cells are block normalized, meaning an intensity value is calculated for a larger region of an image called a block and used to contrast normalize all cell-level histograms within each block. The HOG feature vector for the image is the concatenation of these cell-level histograms.

# run HOG using our grayscale bombus image

hog_features, hog_image = hog(gray_bombus,

visualize=True,

block_norm='L2-Hys',

pixels_per_cell=(16, 16))

# show our hog_image with a gray colormap

plt.imshow(hog_image, cmap=mpl.cm.gray)

%%nose

def test_task4_0():

assert all(hog_image[0] == np.array([0] * 100)), \

'Did you call `hog` on `gray_bombus`?'

def test_task4_1():

assert '_' in globals() and isinstance(globals()['_'], mpl.image.AxesImage), \

'Did you forget to call `plt.imshow` on `hog_image`?'

5. Create image features and flatten into a single row¶

Algorithms require data to be in a format where rows correspond to images and columns correspond to features. This means that all the information for a given image needs to be contained in a single row.

We want to provide our model with the raw pixel values from our images as well as the HOG features we just calculated. To do this, we will write a function called create_features that combines these two sets of features by flattening the three-dimensional array into a one-dimensional (flat) array.

def create_features(img):

# flatten three channel color image

color_features = np.array(bombus).flatten()

# convert image to grayscale

gray_image = rgb2gray(img)

# get HOG features from grayscale image

hog_features = hog(gray_image, block_norm='L2-Hys', pixels_per_cell=(16, 16))

# combine color and hog features into a single array

flat_features = np.hstack((color_features, hog_features))

return flat_features

bombus_features = create_features(bombus)

# print shape of bombus_features

print(bombus_features.shape)

%%nose

def test_task5_0():

assert bombus_features[29999] == 118.0 and round(bombus_features[30000], 3) == 0.053, \

'Did you pass color_features and hog_featuers into the np.hstack function in this order?'

def test_task5_1():

assert bombus_features.shape == (31296,), \

'`bombus_features` does not have the correct shape. Did you setup the `create_features` function properly?'

6. Loop over images to preprocess¶

Above we generated a flattened features array for the bombus image. Now it's time to loop over all of our images. We will create features for each image and then stack the flattened features arrays into a big matrix we can pass into our model.

In the create_feature_matrix function, we'll do the following:

- Load an image

- Generate a row of features using the

create_featuresfunction above - Stack the rows into a features matrix

In the resulting features matrix, rows correspond to images and columns to features.

def create_feature_matrix(label_dataframe):

features_list = []

for img_id in label_dataframe.index:

# load image

img = get_image(img_id)

# get features

image_features = create_features(img)

features_list.append(image_features)

# convert list of arrays into a matrix

feature_matrix = np.array(features_list)

return feature_matrix

# run create_feature_matrix on our dataframe of images

feature_matrix = create_feature_matrix(labels)

%%nose

def test_task6_0():

assert feature_matrix[0, -1] != feature_matrix[1, -1], \

'Did you call `create_features` on `img`?'

def test_task6_1():

assert feature_matrix.shape == (500, 31296), \

'Did you call `create_feature_matrix` on the dataframe `labels`?'

7. Split into train and test sets¶

Now we need to convert our data into train and test sets. We'll use 70% of images as our training data and test our model on the remaining 30%. Scikit-learn's train_test_split function makes this easy.

# split the data into training and test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(feature_matrix,

labels.genus.values,

test_size=.3,

random_state=1234123)

# look at the distribution of labels in the train set

pd.Series(y_train).value_counts()

%%nose

def test_task7_0():

assert '_' in globals() and isinstance(globals()['_'], pd.Series), \

'Did you forget to forget to look at the distribution of labels using `pd.Series(y_train).value_counts()`?'

def test_task7_1():

assert X_train.shape == (350, 31296), \

'Did you pass `feature_matrix` as X into train_test_split?'

def test_task7_2():

assert y_train.shape == (350,) and (np.unique(y_train) == [0., 1.,]).all(), \

'Did you pass `labels.genus.values` as y into train_test_split?'

8. Scale training and test features¶

Our features aren't quite done yet. Many machine learning methods are built to work best with data that has a mean of 0 and unit variance. Luckily, scikit-learn provides a simple way to rescale your data to work well using StandardScaler. They've got a more thorough explanation of why that is in the linked docs.

We needed to split our data before scaling to avoid data leakage, where our model gains information about the test set. Now the data has been split, we can fit the StandardScaler to our training features, and use this fit to transform both sets of data.

# get shape of our training features

print('Training features matrix shape is: ', X_train.shape)

# define standard scaler

ss = StandardScaler()

# fit the scaler and transform the training features

train_stand = ss.fit_transform(X_train)

# use fit_transform to run PCA on our standardized training features

test_stand = ss.transform(X_test)

# look at the new shape of the standardized feature matrices

print('Standardized training features matrix shape is: ', train_stand.shape)

print('Standardized test features matrix shape is: ', test_stand.shape)

%%nose

def test_task8_0():

assert round(train_stand[0, 0], 3) == -1.124, \

'Did you pass in `X_train` to `ss.fit_transform()`?'

def test_task8_1():

assert round(test_stand[0, 0], 3) == -0.749, \

'Did you pass in `X_test` to `ss.transform()`?'

9. Perform PCA¶

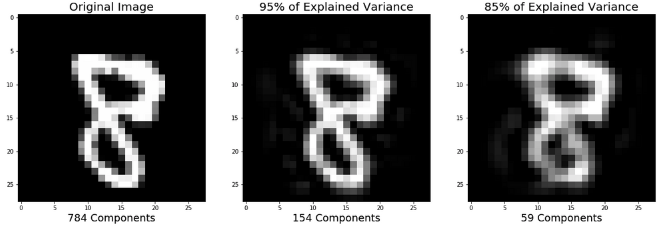

Remember also that we have over 31,000 features for each image and only 500 images total. To use an SVM, our model of choice, we also need to reduce the number of features we have using principal component analysis (PCA).

PCA is a way of linearly transforming the data such that most of the information in the data is contained within a smaller number of features called components. Below is a visual example from an image dataset containing handwritten numbers. The image on the left is the original image with 784 components. We can see that the image on the right (post PCA) captures the shape of the number quite effectively even with only 59 components.

In our case, we will keep 350 components. This means our feature matrices train_stand and test_stand will only have 350 columns, rather than the original of 31,296. Let's start by scaling and performing PCA on our training features.

Note: it may take about 10 seconds for the cell to finish running as PCA is computationally intensive.

# Instantiate a PCA object with 350 components

pca = PCA(n_components=350)

# use fit_transform on our standardized training features

X_train = pca.fit_transform(train_stand)

# use transform on our standardized test features

X_test = pca.transform(test_stand)

# look at the new shape of the transformed matrices

print('Training features matrix is: ', X_train.shape)

print('Test features matrix is: ', X_test.shape)

%%nose

def test_task9_2():

assert round(X_test[0, 0], 3) == 29.419, \

'Did you pass in `test_stand` to `pca_test.fit_transform()`?'

def test_task8_2():

assert X_test.shape == (150, 350), \

'Did you pass in `test_stand` to `pca_test.fit_transform()`?'

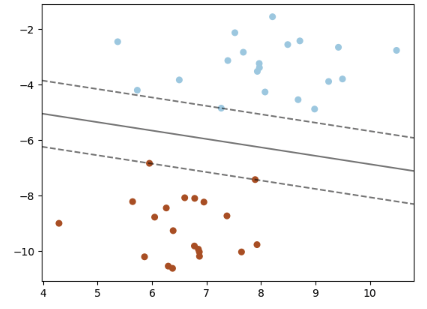

10.Train and score our model¶

It's finally time to build our model! We'll use a support vector machine (SVM), a type of supervised machine learning model used for regression, classification, and outlier detection." An SVM model is a representation of the examples as points in space, mapped so that the examples of the separate categories are divided by a clear gap that is as wide as possible. New examples are then mapped into that same space and predicted to belong to a category based on which side of the gap they fall."

Here's a visualization of the maximum margin separating two classes using an SVM classifier with a linear kernel.

Since we have a classification task -- honey or bumble bee -- we will use the support vector classifier (SVC), a type of SVM. We imported this class at the top of the notebook. We will evaluate performance using the accuracy metric.

# define support vector classifier

svm = SVC(kernel='linear', probability=True, random_state=42)

# fit model

svm.fit(X_train, y_train)

# generate predictions

y_pred = svm.predict(X_test)

# calculate accuracy

accuracy = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred)

print('Model accuracy is: ', accuracy)

%%nose

def test_task10_0():

assert svm.kernel == 'linear' and svm.probability == True, \

'Did you assign define an SVC with a linear kernel and set probability equal to True?'

def test_task10_1():

assert pd.Series(y_pred).value_counts()[0] == 79, \

'Did you generate predictions using `svm.predict(X_test)`?'

def test_task10_2():

assert round(accuracy, 2) == 0.68, \

'Did you calculate accuracy using `accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred)`?'

11. ROC curve + AUC¶

Above, we used svm.predict to predict either 0.0 or 1.0 for each image in X_test. Now, we'll use svm.predict_proba to get the probability that each class is the true label. For example, predict_proba returns [0.46195176, 0.53804824] for the first image, meaning there is a 46% chance the bee in the image is an Apis (0.0) and a 53% chance the bee in the image is a Bombus (1.0). Note that the two probabilities for each image always sum to 1.

Using the default settings, probabilities of 0.5 or above are assigned a class label of 1.0 and those below are assigned a 0.0. However, this threshold can be adjusted. The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC curve) plots the false positive rate and true positive rate at different thresholds. ROC curves are judged visually by how close they are to the upper lefthand corner.

The area under the curve (AUC) is also calculated, where 1 means every predicted label was correct. Generally, the worst score for AUC is 0.5, which is the performance of a model that randomly guesses. See the scikit-learn documentation for more resources and examples on ROC curves and AUC.

# predict probabilities for X_test using predict_proba

probabilities = svm.predict_proba(X_test)

# select the probabilities for label 1.0

y_proba = probabilities[:, 1]

# calculate false positive rate and true positive rate at different thresholds

false_positive_rate, true_positive_rate, thresholds = roc_curve(y_test, y_proba, pos_label=1)

# calculate AUC

roc_auc = auc(false_positive_rate, true_positive_rate)

plt.title('Receiver Operating Characteristic')

# plot the false positive rate on the x axis and the true positive rate on the y axis

roc_plot = plt.plot(false_positive_rate,

true_positive_rate,

label='AUC = {:0.2f}'.format(roc_auc))

plt.legend(loc=0)

plt.plot([0,1], [0,1], ls='--')

plt.ylabel('True Positive Rate')

plt.xlabel('False Positive Rate');

%%nose

def test_task12_0():

assert round(y_proba[0], 1) == .5 , \

'Did you define probabilities using `svm.predict_proba(X_test) and y_proba using `probabilityes[:, 1]?'

def test_task12_1():

assert false_positive_rate.shape == (74,), \

'Did you pass `y_test, y_proba, pos_label=1` into roc_curve?'

def test_task12_2():

assert round(roc_auc, 2) == .74, \

'Did you calculate the roc_auc properly?'

def test_task12_3():

x, y = roc_plot[0].get_data()

assert x[10] == 0.08 and round(y[10], 2) == 0.28, \

'Did you plot the false positive rate on the x axis and the true positive rate on the y axis?'